(Bill Cunningham at Fashion Week, photographed by jiyang Chen, via Wikipedia.)

Bill Cunningham, the beloved fashion photographer for The New York Times, passed away Saturday at the age of 87. Mr. Cunningham spent his entire adult life documenting fashion on the streets of New York City, taking millions of photos of those he found beautiful and interesting. To pay the bills, he worked for “The Man,” as he called the Times, and lived very simply. Everyone knew and loved him, but very few people seemed to know him intimately. In 2011, Bill Cunningham New York, a documentary about his life, was released, and the world got a better glimpse of him, much to his obvious discomfort.

I’ve watched the film several times over the last few years, and watched it again through tears last night. Though he preferred to stay in the background in life, Bill Cunningham’s death leaves a gigantic void in the world of photography and fashion journalism. He was truly an icon, without any exaggeration, and I pray that he knew how much he meant to so many people. Mr. Cunningham possessed an enormous respect for the beauty and individuality of regular people, and he was full of passion and integrity. Some of his best advice came from the recent film, in which he told a colleague, “If you don’t take money, they can’t tell you what to do, kid.”

In the film, we see Bill’s small apartment above Carnegie Hall and his many filing cabinets filled with his entire life’s work. It’s the kind of collection that belongs in a museum, and hopefully that’s exactly where it will end up. When Cunningham was awarded the French Order of Arts and Letters, he said, “It’s as true today as it ever was: he who seeks beauty will find it.”

The New York Times is running an entire section about Bill Cunningham, and I’m linking to this touching article from 2013. Bill Cunningham New York is currently available for streaming on Amazon, and it’s a wonderful profile of this lovely and caring man who sought beauty in all he did.

I recently watched this TedxTalk given by Clara Vuletich, a fashion designer and sustainability expert, and found it insightful and inspiring. Vuletich discusses the links between fashion and sustainability while also emphasizing their obvious differences. She describes the experience of leading a sewing workshop in her neighborhood, where she demonstrated clothing repair techniques to women interested in lengthening the life cycle of their clothing items, and then watching a group of those same women leave her class to go shopping at a local fast fashion retailer. They hadn’t made the connection between fashion and sustainability, she realized, and there’s got to be a better way to educate people about the harsh realities of the fashion industry.

At the same time, Vuletich also recounts visiting garment factories in China, and being struck by the happiness of the young female employees there. Many of the women came from rural areas and were able to earn larger incomes, often sending money home to their families. They enjoyed the friendships made and the experiences of life in a larger city, and Vuletich soon realized that the assumptions she held about garment workers were, in this specific case, false. Vuletich was able to meet with a small group of employees, and while she had initially planned to listen and discuss the problems within the fashion industry, she decided instead to share a sewing technique with them. Her meeting transformed into a group of artists sharing their love of a craft together, and it was a more meaningful experience than she could have imagined.

After returning home, Vuletich designed and created a jacket that took three weeks to sew by hand. The process for her was cathartic, and she describes how she came to a resolution during this time. Sustainable fashion, according to Vuletich, is really about values. Designers must decide what’s important to themselves and their work before they can conform to the larger standards of the industry. Garment workers carry their own sets of values based upon cultures and traditions that might differ from our own. And consumers must decide what we value and take responsibility for our choices when we shop. It’s not enough to call out brands or blame manufacturers for unethical practices when we ourselves are part of the problem. I especially love this point because I believe we as consumers have the power to change things with our own actions.

Vuletich is a huge advocate for the art of hand stitching and encourages her audience to try it as a way to reconnect with our value systems and with the clothes we wear. I’m intrigued by this idea and I’ve realized in recent months that I enjoy those short moments of time when I’m sewing a button back on a blouse or repairing a ripped seam on one of my boys’ stuffed animals (which happens a lot!). I’ve never considered the idea of sewing by hand as anything more than a chore for me, but after watching this talk, I’m curious to explore it more as a mindful exercise.

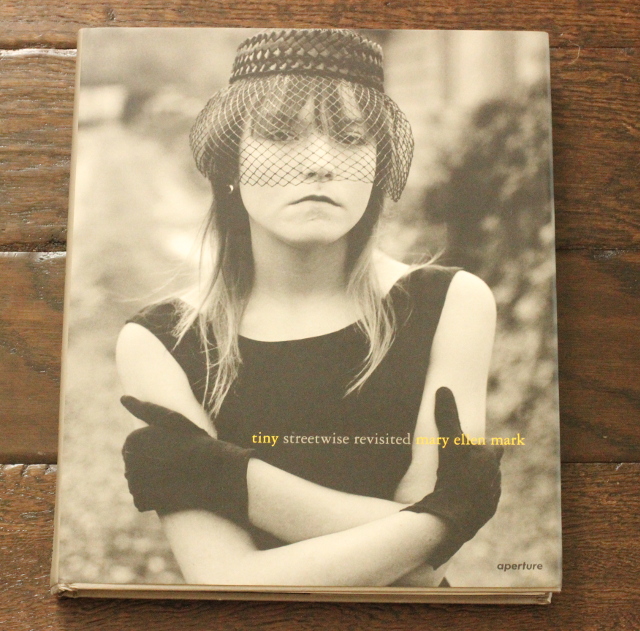

I first read about photographer Mary Ellen Mark in this New York Times article, and I was fascinated with the single image shown in the story, of a young girl dressed for Halloween in a chic black dress, gloves, and veiled hat. The girl’s eyes and expression caught me off guard, and I was struck by her obvious sadness, unhidden even behind her costume. A bit of research led me to Mary Ellen Mark’s book, Tiny: Streetwise Revisited, and I’ve spent the last few days reading and lingering over its photographs.

Mary Ellen Mark, along with her husband Martin Bell, a filmmaker, first began following Tiny and her friends, a group of homeless Seattle teenagers, in the mid-1980s. The joint photography and film project led to the completion of Streetwise, a series of portraits and an award-winning film. Mark and her husband formed a close relationship with Tiny and continued to follow her for decades, as she struggled with poverty and drug addiction while raising ten children. Last year, Mary Ellen Mark passed away, but shortly before her death, the new book was published with additional photos and captions that offer glimpses of Tiny’s life. It’s a beautiful exploration of one young girl’s painful transformation into adulthood, and both Mark and Bell carefully documented Tiny’s experiences in caring and non-judgmental ways.

Coming full circle, Martin Bell recently released Tiny: The Life of Erin Blackwell, with additional footage from the original Streetwise film and further exploration of Tiny’s life. I hope to eventually see the first film, as well as this new iteration. The entire project became the life’s work of both Mary Ellen Mark and Martin Bell, and their enduring friendship with Tiny, the main subject, is fascinating. Three different people from very different backgrounds and experiences found each other along the way and grabbed hold, and that’s a story worth sharing.

And right now, as we’re mourning the horrific mass shooting in Orlando, it’s difficult for a lot of us to find the right words to express our feelings. Leah, my blog friend, made a lovely and brave attempt, and it’s also worth sharing.